A Connection with the Rebbe z’l

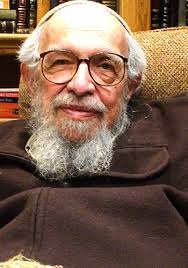

Here’s the first part of a precious sharing from Reb Zalman, alav hashalom, and his first encounter with the late Lubavitcher Rebbe, Reb Menachem Mendel Schneerson, alav hashalom. The teaching came on 3 Tammuz 5766, the Rebbe’s 12th Yortzeit, (June 29, 2006). The source is the DVD, “What’s New in Jewish Renewal, 2006”, disk 3, Copyright © Spirit of the Desert Productions. (Edited by Gabbai Seth Fishman)

I want to make a connection with the Rebbe, with Reb Menachem Mendel, (it’s his Yorzeit today), and I’d like to urge you to do the following:

If you have, anywhere, a hope, a concern, something for which you would go to a Rebbe with a qvittel so that he would pray for you, keep that in mind and, during the second half today, we are going to chant the ana b’choach and send off, in a sense, sort of like hitting the enter button to send off your request.

And so, in all the things that I want to do today, I want to do it really logged on to that website, to what I learned from the Rebbe and some of the things that happened to me in encountering with him.

[To begin, I’ll tell you when I first saw him:] In the beginning, I thought of him [as the Moroccan]. I was living in Marseilles, France; the year was 1940 and 41.

Reb Menachem Mendel Schneerson

We were released from one of the internment camps and made our way to Marseilles and there was a stiebele there on Rue Convalescent. Upstairs was a soup kitchen for the refugees and downstairs was a little shul where we met to davven.

All the refugee people would be in that shul. And just a handful of these wore long black coats, kapotes, and hats that were black hats, often made of velour, real hasidishe hats and, of course, beards. In these days one didn’t see many beards. (At the same time, in America, there was the House of David, a baseball team and they used to have beards as well, but it was kind of rare to see Jews with beards in those days. As I recall, they really came in at the same time as the beats with the long hair; before that, there really were few beards.) So I thought: Beards and black coats go together.

But then, a certain young man came into that shul with a very nice stature, a good, open, slightly severe though also friendly face, wearing a gray fedora hat and gray suit. And I looked at him [thinking]: “Who is this guy? Not a [hasid] because beard, yes; black coat, no. Who is this guy?!?”

He captured my attention and so, when I saw him at a later time coming into that shul and from time to time sitting with a Moroccan chacham / sage who was there, too; when I saw them studying together, and heard him saying what sounded to me as translation of the material in the gemara into either a Hebrew that I could not quite understand or Arabic, I made it up that this fellow was a Moroccan as well.

One day during this period of my life, (it was, as I recall, Parashat Vayechi [Jan 11, 1941]), and I went for a walk in Marseilles and spent some time in a very beautiful, old, French shul with cloister walks, similar to the Rashi shul, with that really wonderful ancient Romanesque type [of architecture].

It was on that day when I first heard the practice of getting called to the Torah and turning to the people saying: “Adonay imachem” / may the Lord be with you, and the people answering back, “Yivarech’cha adonay” / may God bless you.

Now where does this come from? From the book of Ruth where it says that Boaz comes into the field, meets his workers. Just imagine labor relations like that, the boss saying, “Adonay imachem“, and the people saying, “Yivarech’cha adonay“! What a wonderful way of greeting one another! It also helps one to understand clearly why that same sense in Dominos vobiscum was taken over in the church; Adonay imachem. There’s a beautiful, deep meaning in it as though asking, “Where am I going to find God; where is Adonay?” “Imachem!”, there with you, connecting with your neshamas / souls and then, your neshamas connecting with God. It’s “Adonay imachem“. And then, when people answer, saying, “yivarech’cha adonay“, it’s like, “And may you be connected up there to be a breicha / a channel to bring us down that which comes from above”.

I made my way back to the little shul on Rue Convalescent, coming in already after minchah, (I did minchah and had had an aliyah in that other shul), and there, with a particular kind of hasidic black hat that was called pork pie, and a red beard, sitting, one leg across the other, was a person I had not seen before, saying:

יערף כמטר לקחי תזל כטל אמרתי / “yairoyf kamawtor likchi tizal katal imrawsi” / My lesson will drip like rain; My word will flow like dew (Deut 32:2).

Now, to my ear that was used to “yairuf kamutor likchi tizal k’tal imrusi” his way of pronouncing and intoning was unfamiliar, very Galicianer-like, and I asked:

“Who is this person up there?” And someone said, “He is Reb Zalman Schneerson.”

I knew already of Reb Shneur Zalman of Liadi because of some people I met in Belgium.

And then they told me he had been a Rabbi in Paris, now in Vichy and that he traveled back and forth between Vichy and Marseilles working for the refugees.

On that occasion, he was giving a wonderful teaching about two kinds of Torah:

First, there’s the Torah in which God says, “I give this away to you”:

כי לקח טוב נתתי לכם תורתי אל תעזבו / ki lekach tov natati lachem torati al taazovu / For I gave you good teaching; forsake not My instruction. (Proverbs 4:2)

There is the torah / teaching I give away to you.

But when you only look at that torah that is given away to you, you might forget from Whom it comes and you might think it’s your torah. So there is another level of torah that comes down from heaven that’s torahti / My torah.

You still can feel that God is the One who gives it: Al Taazovu / forsake not My instruction. If you hold onto the torah that God gives you and know that S/He is the source of the Torah, you will not be forsaken.

Well, it touched me a great deal. Here, he talked about the outer part of the Torah, which is nigleh / revealed and the inner part of the Torah which is nistar / the hidden one, the kind of things that hasidus and kabbalah are about and I was [really moved so after he was done,] I walked him to his hotel.

He asked me what I wanted from him? And I said:

“I’m one of several teenage boys here and we want to learn Torah but don’t have someone to teach us. We are, after all, not busy; we live on the dole with nothing to do? Would you help us with setting up a yeshivah?”

He took it to heart.

There was another man there, Hayyim Aryeh Silberstein whom he enlisted. He set it up for us to study a half a day in that little shul. After the davvenen was over we went upstairs to the soup kitchen to get our food and then, we would go back down and study.

The gemara we began with was Ketubot dealing with the way to write marriage contracts.

Choices of what was to be studied, in a situation like this, were not necessarily according to what we would have chosen. In reality, there were only a few gemara‘s around in that shtiebel of the same masechet / tractate; so that’s what we studied.

Reb Zalman Schneerson was very good to us. He came from time to time and taught us Torah.

One day, he announced: “Tu B’shvat [February 12, 1941] I can’t be here, so I’m going to send you a guest.”

Tu B’shvat arrives and we are sitting down, singing a niggun, having some fruit and a little bit of schnapps, when in comes his “guest”: My Moroccan!

We make him a place and he begins to say, “Vos lernt ihr” / what are you studying, speaking Yiddish!

So we told him we are studying ketubot.

[First he] said “l’chayyim“, made a brachah over the fruit, shehecheyanu, and then began his teaching:

“The first mishnah begins by saying, ‘A virgin is married on the fourth day,'” meaning on Wednesday.

And the gemara goes on to tell why: Just in case he found that she was not a virgin he could go the next morning, when the court is in session, and complain at the court on Thursday (I’m giving you the p’shat of that now, the simple meaning that’s there.)

The talmud wants to find out, “Why not also on Sunday because the court is sitting also on Monday?”

And they say, “No. But you have to give a girl who’s getting married three days to make herself pretty.”

Now, what happens if she is a widow? Then it goes on to say that she gets married on Thursday which means that she has, on that day, the benefit of the blessing that God gave to the birds and fishes when He said “p’ru ur’vu u’milu et hamayim“, so they get this blessing of fecundity.

But what happens if she’s a divorcee? Then, she gets married on a Friday. (It’s not an issue of complaining later on she wasn’t a virgin; she was married, she is divorced, that’s not a problem.) So, she gets married on Friday. And why on Friday? Because, God said to Adam and to Eve, “peru ur’vu umillu et ha-aretz,” also to be fruitful and to multiply.

Now we already knew the gemora up to here so that wasn’t anything new.

So he continues:

Betula / virgin, Israel who is in relationship to God like a young woman, they say she is getting married, b’yom harivii in the fourth millennium.

Because, the Rabbis have said:

שית אלפי שנין דהוי עלמא / sheet alphei sh’nin d’hvey alma / six thousand years is the world.

The first two thousand years are the wild and woolly ones, the second two thousand years are the Torah ones, and the third two thousand years are the years of Moshiach.

And this relationship of God and Israel is like a marriage.

So when was the engagement, תנאים / T’na’im?

So the Rebbe said: T’na’i HaKadosh Baruch Hu b’maaseh b’reishit / when the world was created God made those T’nai / conditions, the engagement happened [in this way]:

[God had said:] “There will be a time you will be at Mount Sinai and I will give you the Torah and then will be that part of the consummation that has to happen.”

Why? Because we say, “asher kiddishanu bimitzvotav“, i.e., the Mitzvahs are the ring that God gave us for kiddushin.

You hear that? That sense is so wonderful!

So, the wedding was supposed to be then:

שני אלפים תורה שני אלפים ימות המשיח / shnei alaphim tohu shnei alaphim torah:

So after the two thousand years of Torah we should have had the final nissuim, the final wedding and the marriage should have been at the end of the fourth millennium so that we would have two millennia in which we can celebrate Moshiach–zeit’n.

And why is it that you can’t have the wedding on Sunday right at the beginning? It is because you give a girl three days to make herself pretty. And what is the three days in this respect? To acquire Mitzvahs and to learn and to gather the hidden sparks that have fallen into exile, into kelippah. And by going and doing our holy work, we redeem the sparks. Every spark that we redeem is like a beautiful diadem that we wear to the wedding.

So we are being given the three days to pick up the sparks.

The wedding would have been [already] if Israel would have been on the level of Betula / of the virgin. But if you read Hosea and other Prophets, you will see how Israel was not in that situation.

So when is the redemption to come if she is like a widow? Because it says:

איכה ישבה בדד היתה כאלמנה / eicha yashva vadad hayita ka’almanah / … she was like a widow.

When does a widow get married? Bayom Chamishi.

So about a thousand years ago we should have already had the final redemption.

But what happens if:

כי מצא בה ערות דבר / ki matza bah ervat davar / he found that there were some things that were not so good, that there were sins there (Deut 24:1).

כי בפשעיכם שלחה אמכם / ki b’pisheichem shulchah imachem / your mother has been sent away, divorced on account of your sin (Isaiah 50:1).

Israel is now like a divorcee. The wedding should be on Friday.

And it is Friday now [the sixth millennium, year 5701] and a divorcee is to be married on Friday.

And then he started coughing, his way to hide his crying. He didn’t want to show it.

And he said:

“It’s already getting so late on Friday, when is it going to happen?”

And this was in 1941. You can imagine just [how it was then], the [Warsaw] ghetto uprising just a couple of months later.

It was a difficult, difficult time.

I still didn’t know who he was.

When he left, somebody told me that he was a Rabbi Schneerson also, Reb Menachem Schneerson, and that he lived at that time in Nice, in France, at that other city.

I managed to make it to New York the day before Pesach that year [April 10, 1941] and, as soon as I could, I wanted to have an audience with the Lubavitcher Rebbe, his father-in-law. I felt I needed an excuse: I said that I am bringing regards from his son-in-law.

It was a marvelous encounter!

There is something that the gemara says:

אין האשה כורתת ברית אלא למי שעשאה כלי / eyn haishah koretet brit ela im mi she-asa’ah keli / a woman does not make a covenant except with the person with whom she is first in a loving relationship (Sanhedrin 22b). This gemara seems fitting to characterize my coming to the Rebbe with that openness and my desire to learn from him and be his hasid.

And in a few moments he had it all fixed up: I was, at that time, working as a furrier; and he got a job for me (although only sixteen years of age then, the family really needed the income I could earn). My brother was enrolled in the Yeshivah, my sisters, in Shulamith School: He fixed us up one-two-three. He called the gabbai in and told him to do such and such, to call these people make sure we are [set up].

Then he turned to me and said:

“They tell me you have regards for me.”

So I told him that I had been there in the shul for Tu B’shvat and that he came and taught us. And of the little yeshivah we had. He was very happy to hear of it.

“And what did he say?”

I started to give it over.

A few times he made a face as if to say, “No, not quite. But, [yes], good!”

Finally, he gave us a brachah and I walked out.

I was crying.

People asked why.

When you don’t know, you make up a reason, right? So I made up a reason:

“Because he was paralyzed! ‘S – p – e – a – k – i – n – g w – a – s h – a – r – d f – o – r h – i – m,’ I imitated.”

This was the way he spoke.

I was saying, in effect:

“Oy! I’m crying because of what the Bolsheviks did to him when he was arrested and was tortured by them, etc. That’s why.”

But later on, I found out how they talk of it in Hasidus:

It is like when a candle gets close to a big flame.

When you come and see the Rebbe there is something about:

“Oy! I was thirsty!”

a cry of a relief and a sense of saying:

“Now I will not have to wander any more, now I’ve got my direction.“

A few months later, he arrived in the United States. I was enrolled in the yeshivah by then.

He looked at me and then he said:

“Rue Convalescent, Tu B’shvat, you were sitting over here.

“Do you remember what I said?”

Oy!

I started to go over what I could remember. He corrected me a couple of times; and that was wonderful!

I want you to know that sometimes people look at things having to do with Renewal as if it were a REVOLUTION.

I want to say, “No! It’s an EVOLUTION.”

Because, as you heard me give over this lesson about phases in history and that there is a development going from the wild and woolly days to the days of Torah to the days of Mashiach, the days of the resurrection, one has a sense that there is an evolution going on.

If one goes by this, one has to say, in addition, that there was a paradigm shift when we moved out of Egypt, from the wild and woolly days, into the Torah days; a real shift.

Consciousness shifted then, just as it happened during the axial age later on, a time when consciousness shifted. A few people got it at first; we got it then.

The notion that consciousness shifts is something that stayed with me very strongly from that day until now.

אנא, בכח גדלת ימינך תתיר צרורה: אב”ג ית”ץ

קבל רנת עמך, שגבנו, טהרנו, נורא: קר”ע שט”ן

נא גבור, דורשי יחודך כבבת שמרם: נג”ד יכ”ש

ברכם, טהרם, רחמי צדקתך תמיד גמלם: בט”ר צת”ג

חסין קדושׁ, ברוב טובך נהל עדתך: חק”ב טנ”ע

יחיד גאה, לעמך פנה, זוכרי קדשתך: יג”ל פז”ק

שועתנו קבל ושמע צעקתנו, יודע תעלמות: שק”ו צי”ת

ברוך שם כבוד מלכותו לעולם ועד ד