A Trip To Brooklyn

Dear Friends:

Here is the article, written by me in the summer of ’91, and describing my trip with Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, a’h, together with his youngest son, Yotam, and our encounter with the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Reb Menachem Mendel Schneerson, a’h. [NOTE: If you scroll down to the end, you will see the video of the Rebbe’s words to Reb Zalman.] Gabbai Seth Fishman

A TRIP TO BROOKLYN

Reb Zalman wanted Yotam to meet the Rebbe and also wanted to give the Rebbe a copy of Spiritual Intimacy: A Study of Counseling in Hasidism, a book Zalman wrote about the holy love that exists between a Rebbe and his students. I was to come along to help in the trip, and to ask the Rebbe for a blessing for myself and my wife Anna on our then, upcoming wedding.

On Sunday, August 18th, 1991, at 8AM, I met Reb Zalman and Yotam, and we set out on the drive to Brooklyn. I was curious to learn about Zalman’s time spent in the Lubavitch community and asked many questions as we drove.

“When did you first meet the Lubavitcher Rebbe?,” I asked Reb Zalman.

“We were living in Marseilles during the war. One of the Schneersons came to our shul. It was Parashat Vay’chi. The rabbi walked with a limp; what we called a ‘Jacob walk.’ He wore a black pork-pie hat. This was R’ Zalman Schneerson. I told him that there were a few of us who wanted to have a class and asked if he could send someone. He said he would arrange it.

“When the day for the class arrived and the teacher came in, I remembered having seen him before on several occasions and I had concluded that this man wasn’t Ashkenazic, since his beard was neatly trimmed, his clothing fine European, and I had never heard him speak Yiddish. He had an impressive knowledge of science and philosophy, and his French was excellent. But now, this mysterious man appeared at the door and spoke Yiddish! This was the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Reb Menachem Mendel Schneerson. The class he taught us on that day was from tractate Ketuboth, the book in the Talmud about the laws of marriage contracts. His teachings related this tractate to a marriage between God and Israel.

“I’m bringing the Rebbe a copy of my new book. It is about the special love that exists between a Rebbe and his student and how this love is holy.”

“Zalman, did you hear that the Lubavitcher Rebbe has had a house built in Eretz Yisroel which is supposed to be the house for the Messiah?” I asked. “The Lubavitcher Rebbe says the Mashiach is coming this year.”

“Shh.. I’m concentrating my positive energy for this visit. I don’t want to think of the bad.”

He was quiet. I said, “You must be experiencing quite a few emotions about the trip.”

“Oy,” he said. “Yes. Through the whole gamut of feelings.”

The ride was smooth, except for a minor traffic jam when we were already in Brooklyn. Yotam started getting nudgy. (My car had no air conditioning, and the day was sweltering.) I asked him to tell me about the “Mutant Ninja Hassids,” an imaginative group he had helped create at the last Kallah, to take his mind off the heat.

Finally, after traveling over the bumpy, broken-up streets of Brooklyn, we arrived in Crown Heights, and parked a block from our destination. I put on an arba kanfoth (tzitzith), a white shirt and a suit jacket. Zalman was dressed in a more comfortable outfit including sandals and a funky cap.

“I want the Lubavitcher Rebbe to see me as I am,” he remarked.

Costume: 20th century renewal, not 19th century businessman.

We walked into the building, the World Lubavitch Headquarters. Chossids were standing at the door asking us eagerly, in Yiddish, whether we had yet fulfilled the mitzvah of laying tefillin that day. Signs were on the walls indicating the time until which one could fulfill the mitzvah of reciting the Shema. We walked to the line for waiting to meet the Rebbe, and as we walked, we were accosted by a stream of beggars and hawkers, many speaking in Yiddish, some saying, “Give a dollar to bring Mashiach.” An old, old, well-dressed man with a long gray beard stopped us and asked for tzedaka. Zalman gave him a dollar. After several similar requests, Zalman put me in charge of his change purse.

“Give to whomever you feel should have it.”

Not far from where we stood, was a clothesline with a plastic shower curtain hanging, a makeshift mechitzah. Throughout the afternoon, someone would pull down on the rope bringing to view the hundreds of women who had also come on that day.

“The line is open to anyone,” Zalman explained. “First the Rebbe meets the women and then the men. He gives you a dollar bill, a blessing which encourages each person to perform acts of tzedaka and mitzvoth.”

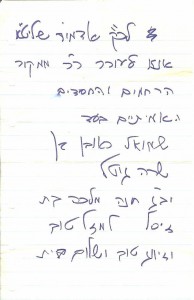

Zalman wrote my petition in Hebrew and handed it to me.

“Copy this. It is the note you will give the Lubavitcher Rebbe. It asks him to pray on your behalf for a successful marriage.”

The text Zalman handed me, consisted of three blessings: mazel tov (good luck), zivug tov (good union) and shalom bayith (a peaceful home). (These phrases were later written onto the chuppah used for our wedding ceremony prepared by Devorah Schiff.)

We remained there with no movement for many hours, subjected to cigarette smoke and a good deal of shoving. Periodically, large groups of men would cut in front, jumping over the wall which served as a barrier.

A chossid was standing nearby with a baby carriage.

“Do you know Simon Yakobson?,” Zalman asked in Yiddish.

Yakobson was an old friend, I thought.

“Who are you?,” the man asked.

Zalman identified himself.

“You are Zalman Schachter?!,” the man said with surprise. “I have a dear friend who studied with you in Los Angeles. I’m happy to meet you.”

Zalman made the best of the time we had to wait. Leaving the line with Yotam to purchase food and drink, Zalman returned carrying a book he had obtained from one of the shelves in the room, Likutei Torah, by Schneur Zalman of Liadi, volume Vayikra. He started teaching to us.

He spoke of two types of tzaddikim, one likened to Leviathan (the great sea monster) and one to Behemoth (another gargantuan monster). Leviathan, swimming in the depths, is likened to a tzaddik living in a cave, who cannot buy a challah or light candles for Shabbos, yet, who worships Hashem through his powerful intention and love for God. The Behemoth is like a tzaddik who has all ingredients to perform mitzvoth available; but whose consciousness does not go beyond the details. Each of these tzaddikim is incomplete. They will merge in Olam Habah.

As Zalman read, the crowd, falsely anticipating an end to the waiting, pushed tighter and tighter around us.

“Hey, not so close!,” Zalman yelled at one man as the man leaned into him.

At another point during the long wait, Reb Zalman sang a Niggun. He smiled as he sang. All the pushing; all the cigarette smoke: none of the inconveniences seemed to matter. Zalman was unconcerned; and he had an infectious spirit. Most standing nearby watched curiously; a few sang along.

We waited with no movement, tired of standing. We heard a boy, several years older than Yotam, starting to cry. People in line were pushing in every direction. Sitting in a corner of the davening space, an old, well-dressed beggar with a long gray beard spit a big gob onto the floor. Groups of young men increased their smoking.

A chossid appeared on a raised surface in front of the room in view of both the men and women and asked for quiet. A hush descended as everyone thought that an announcement concerning the Rebbe was to be made. Instead, the chossid spoke at length in Yiddish about Rosh Hashonna and shofar, shouting in a high-pitched, crackly voice. The noise of the crowd resumed and his voice became harder and harder to discern from the noise. When he had finished his sermon, he blew the shofar, sounding a long blast. Some young foreign boys from the line ran up to the place where the chossid had just finished his sermon and started dancing, gyrating their hips facing toward the women’s line.

Eventually, the line started moving, and Yotam realized he had to go to the bathroom. But there was no possibility of this now. We moved straight ahead, being pushed forward by a mass of humanity.

As the crowd moved forward, the pushing became more intense. Concerned we would become separated, Zalman suggested we hold hands and not let go.

“Watch it!,” he shouted. “There’s a little boy down here. Hey!”

We somehow managed to stay in a group as we rounded a corner and descended some stairs. We found ourselves in a narrow walkway, able to fit only single-file: Yotam was first, Zalman next and then I. At the end, we reached a vestibule with a fire-door off on one side.

“I used to use the space behind that door when I needed seclusion; to meditate,” Zalman told us.

It seemed every inch of this place was filled with some memory or other for him.

The air changed. We were in the inner sanctum. Suddenly cool and clean, one could see a brightly lit, nicely adorned room with rich furnishings and fine art. Half a dozen chossids were standing around a lectern with a pile of dollar bills on it; and in the middle was the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Schneerson.

As we came closer, a chossid took my note.

“Is it for the Rebbe?,” he asked.

I nodded. He threw it into a box on the lectern.

The line was moving quickly now. The Rebbe handed out a dollar and each man passed on and out. I was sad my note was gone. I had thought I would be able to give it to the Rebbe. The petitioning I expected was not happening. It seemed rather mechanical.

“Perhaps there were too many people in line on this particular day,” I thought; or maybe they were running late. The Rebbe seemed tired.

The line kept moving until Reb Zalman stood before the Lubavitcher Rebbe. A noticeable change of expression came over the Rebbe’s face: a look of love and surprise. He handed Zalman a dollar bill and began speaking in Yiddish. As he spoke, he gave Zalman a second dollar bill and then a third. The other chossids in the room listened with interest to the Rebbe’s words and marked as he gave Zalman the third bill. Although they wanted to keep the immense line moving quickly, they listened attentively.

After the Rebbe finished speaking and Zalman had presented him with the copy of his then brand new book, Spiritual Intimacy, Zalman and Yotam walked to the exit as I received my dollar bill and followed them out of the building into the sunlight.

“That was wonderful,” Zalman remarked.

Not understanding Yiddish well, I was curious to learn what the Rebbe had said. But I decided to wait till later. Instead, I asked Zalman what would happen to my note.

“The Rebbe goes to the grave of his father-in-law every Sunday afternoon and prays that the departed neshamah might intercede with the Kadosh Baruch Hu on behalf of those who came today. Your note will be read at the graveside.”

On the street were merchants and beggars, rabbis and women with sheydels. We walked over to a vendor offering to laminate the dollar bills, inserting a large picture of the Rebbe covering up Washington’s. Zalman had Yotam’s bill laminated so he might not misplace it and also for a memento of the trip.

Walking in the street, we met a chossid Zalman recognized. The man was obviously from Philadelphia, though I had not seen him before.

“Zalman,” he said, “I see you more here than in Philadelphia.”

After we had passed him, Zalman said:

“He looked at me as if to say, ‘Dressed like this, you go to see the Rebbe?'”

Another chossid came to speak to Zalman. Zalman had earlier pointed him out to us as the brother of the Rebbe’s secretary.

“Oh, Zalman, remember back in the forties, when you used to come to my parent’s house? One time you told me something, and I will never forget it. Those were wonderful days.” He then reminded Zalman of a long story from his youth, the details of which I couldn’t quite catch. When he finished, Zalman said:

“I gave you that advice? Good!”

A hawker came by, saying he had located Simon Yakobson, the person for whom Zalman had been searching throughout the day. I assumed Yakobson to be an old friend of Zalman’s and was looking forward to hearing more stories about his early days with the Lubavitchers.

According to the hawker, Yakobson was to be found on the third floor of a building around the corner. It was an old and rickety-looking structure. Climbing to the third floor on a dingy staircase, we entered a large office filled with pictures of the Lubavitcher Rebbe and other posters mostly in Hebrew. We were in the room in which Lubavitcher pamphlets and newsletters were formatted and arranged.

Yakobson was not the old acquaintance I had expected. He was a young man, the Lubavitch computer maven. Zalman had wanted to meet with him to discuss current technology in desktop publishing for Hebrew publications. [NOTE: In 1991, I didn’t yet know of Rabbi Simon Jacobson, who has subsequently published several books, a major writer on the works of the late Rebbe and his teachings. Gabbai Seth]

On the way back to Philadelphia, we pulled into a rest stop. Seeing Zalman’s yarmulke and beard, a Jewish man asked him if he was a Lubavitcher. After concluding his chat, Zalman later commented to me:

“The Lubavitchers are highly regarded by Jews in general for the work that they do. The simple act of the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s handing out dollar bills is a powerful statement. It is clear to me that we at P’nai Or also have something to offer this Jewish man to whom I was just speaking. How can we better reach these people so they will know we are here?”

Yotam and I were still curious to learn more about what had been said when the Lubavitcher Rebbe was talking to Zalman.

“Could you explain what the Yiddish meant?” I asked.

Zalman explained that the Rebbe had told him that he (Zalman) had been away from there for a long time. Soon it would be the month of Tishri. Since Zalman is a kohayn, that means he would be giving blessings to others. Thus, he gave him an extra dollar for the blessings Zalman would be giving.

The Rebbe gave Zalman a dollar for himself, one for Zalman’s son, and one for the blessings Zalman gives to all of us who have been blessed to know him and to learn from his wisdom. It is obvious that the Rebbe holds Zalman in high esteem; and also obvious that the Rebbe occupies a special place in Zalman’s life, as well.

But, why had it been so long since the last visit? What was the rift and whence had it come?

Zalman explained:

“It was twenty-five years ago. I was traveling around giving lectures at synagogues. A woman from a Jewish newspaper came to one of the synagogues where I had been a speaker in previous weeks. When she saw the titles of the talks, (one was titled “Moses and McLuhan,” the other, “The Kabbalah and LSD”), she followed up on it in the interest of turning it into some news. She called the office of the Lubavitcher Rebbe and asked whether the Rebbe had given permission to R. Zalman Schachter to take LSD. Two weeks afterward, a prominent Jewish magazine published a statement from the Lubavitch office which essentially said my s’micha was not straight.”

Even though s’micha cannot be withdrawn, (nor ever was, as the published statement seemed to suggest), this was a significant turning point in Zalman’s career.

From a young Lubavitch man who shows up from time to time at Zalman’s classes, I learned that among Lubavitchers, some stories portray Zalman as a seer and a tzaddik; some as a teacher of sacrilege. But the Rebbe himself would ask, “Did you see Zalman? Why did you not go to him?”

(Originally Published Winter 5754 in the Pnai Or Publication, “The New Menorah”)

ADDENDA, 2/21/2016

I obtained the video of the event from Chabad’s JEWISH EDUCATIONAL MEDIA (JEM). Here is the actual footage from the day plus a translation of the Rebbe’s words below.

NOTE: Here is the text transcribed from the video

ברכה והצלחה

א לאנגע צייט אייך ניט געזען

איהר זענט דאך א כהן

נו, וועסט מסתמא דוכן’ן

עס געהט זיך ר”ה און א גאנצע חודש

נישט פארגעסן דוכענען. “ואני אברכם

ס’זאָל זיין אין א גוטע שעה. בשורות טובות

TRANSLATION OF THE REBBE’S WORDS TO REB ZALMAN:

“Blessing and Success.

[NOTE: this was the standard blessing of the Rebbe. To which he added:]

“It’s a long time since I saw you. You are, of course, a Kohen / Priest. Nu, therefore, you’ll most likely dukhen / bless the people with the Priestly blessings – [since] Rosh Hashanah and an entire month [of Tishrei] is approaching [in 3 weeks]. [So] don’t forget to dukhen. ‘And I will bless them.’

[NOTE: This text is the coda of the Priestly Blessing, (Numbers 6:27)].

“May it be in a good hour. Good tidings.” [Translation: Baruch Jean Thaler, Lazer Mishulovin, Ari Greenberg, Stephen Cohen.]

July 19th, 2016 at 8:14 pm

During a class I took with the esteemed author and teacher Joel Segel at the 2016 Aleph Kallah, he shared Reb Zalman’s version of what the Rebbe said, as documented in his wonderful book, “Jewish with Feeling” and gave permission to include it here:

Reb Zalman: I received a third important lesson about blessing from Reb Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the last Lubavitcher Rebbe. When he got older, the Rebbe took up the practice of giving out dollar bills for charity on Sunday afternoon, and people would line up for hours for the chance to exchange a few words. The Chabad people took a photograph of each person who came up, and I still have the picture from the time I joined the line. Someone whispered my name to the Rebbe, but he didn’t need it. He looked at me with a smile and handed me a dollar. And then he said to me, “Reb Zalman, you’re a Kohen, a priest. Please keep me also in mind when you’re reciting the Priestly Blessing during the High Holidays.”

I want to tell you, never have I felt such empowerment as a Kohen as I felt at that moment, when the Rebbe asked for my blessing. But I didn’t understand his request as saying that he needed my help. He was offering a teaching: When you get up there, and raise your arms, and begin the blessing, don’t do it as a routine, just because the chazan is prompting you to say, “Yevarekhekha!” Keep specific people in mind. Bring blessings down for them. He was offering himself as a model for that.